I decided it was time to release a proper PyArmor unpacker. All the ones that currently are public are either outdated, not working at all or only giving partial output. I plan on making this one support the latest version of PyArmor.

Please star the repository if you found it helpful. I would really appreciate it.

There are 3 different methods for unpacking PyArmor, in the methods folder in this repository you will find all the files needed for each method. Below you will find a detailed write-up on how I started all the way to the end product. I hope more people actually understand how it works this way rather than just using the tool.

This is a list of all the known issues/missing features. I don't have enough time to fix them myself so I heavily rely on contributors.

Issues:

Unsafe way of stopping the second marshal.loads trigger (see write-up)Fixed by issue #9Async code objects don't get invoked correctly -> programs like discord bots can't be unpackedFixed by issue #19From Python 3.10 and higher the absolute jump indexes have been divided by 2 to save storage, we have to add support for that.Fixed by issue #3

Missing features:

- Unit tests

- Static unpacking for versions below 3.9.7

Multi file supportFixed by issue #11- Better logging

Better prevention of accidentally executing the program for method #3Fixed by issue #9

IMPORTANT: USE THE SAME PYTHON VERSION EVERYWHERE, LOOK AT WHAT THE PROGRAM YOU ARE UNPACKING IS COMPILED WITH. If you don't, you will face issues.

- Copy all the files from the method #1 directory into the same directory as the file you want to unpack.

- Run the file you want to unpack

- Use an injector (I recommend Process Hacker 2) to inject https://github.com/call-042PE/PyInjector (Choose the x64 or x86 version based on your application)

- Run the

method_1.pyfile - Now you can run the partially unpacked program using

run.py

- Copy all the files from the method #2 directory into the same directory as the file you want to unpack.

- Run the file you want to unpack

- Use an injector (I recommend Process Hacker 2) to inject https://github.com/call-042PE/PyInjector (Choose the x64 or x86 version based on your application)

- In the

dumpsdirectory you can find the fully unpacked.pycfile. - (Optional) Use a decompiler to get the Python source back, since currently 3.9.7 is the minimum version you will have to use: https://github.com/zrax/pycdc

NOTE: Don't use the static unpacker for anything below version 3.9.7, The marshal.loads audit log was only added in and after 3.9.7. Any contributors are welcome to add support

- Copy all the files from the method #3 directory into the same directory as the file you want to unpack.

- In the terminal run this:

python3 bypass.py filename.pyc(replacefilename.pycwith the actual filename, obviously) - In the

dumpsdirectory you can find the fully unpacked.pycfile. - (Optional) Use a decompiler to get the Python source back, since currently 3.9.7 is the minimum version you will have to use: https://github.com/zrax/pycdc

Contributions are really important. I don't have enough time to fix all the issues listed above. Please contribute if you can.

If you like you can also sponsor me on Github: https://github.com/sponsors/Svenskithesource/

This is the long-awaited write-up about the full process I went through to deobfuscate or rather unpack PyArmor, I will go through all the research I did and at the end give 3 methods for unpacking PyArmor, they are all unique and applicable in different situations. I want to mention I didn’t know a lot about Python internals so it took a lot longer for me than for other people with more experience in Python internals.

PyArmor has a very extensive documentation on how they do everything, I would recommend you read that fully. PyArmor essentially loops through every code object and encrypts it. There is a fixed header and footer though. This depends on if the “wrap mode” is enabled, it is by default.

wrap header:

LOAD_GLOBALS N (__armor_enter__) N = length of co_consts

CALL_FUNCTION 0

POP_TOP

SETUP_FINALLY X (jump to wrap footer) X = size of original byte code

changed original byte code:

Increase oparg of each absolute jump instruction by the size of wrap header

Obfuscate original byte code

...

wrap footer:

LOAD_GLOBALS N + 1 (__armor_exit__)

CALL_FUNCTION 0

POP_TOP

END_FINALLY

From the PyArmor docs

In the header there is a call to the __armor_enter__ function, which will decrypt the code object in memory. After the code object has finished the __armor_exit__ function will be called which will re-encrypt the code object again so no decrypted code objects get left behind in memory.

When we compile a PyArmor script we can see there is the entry point file, and a pytransform folder. This folder contains a dll and an __init__.py file.

dist

│ test.py

└───pytransform

| _pytransform.dll

| __init__.py

The __init__.py file doesn’t have to do much with decrypting the code objects. It is mostly used so that we can import the module.

It does some checks like what OS you're using, if you’d like to read it, it’s open source so you can just open it like a normal Python script.

The most important thing it does is loading the _pytransform.dll and exposing its functions to the Python interpreter’s globals. In all the scripts we can see that from pytransform it imports pyarmor_runtime.

from pytransform import pyarmor_runtime

pyarmor_runtime()

__pyarmor__(__name__, __file__, b'\x50\x59\x41\x5...')This function will create all the functions necessary to run PyArmor scripts, like the __armor_enter__ and __armor_exit__ function.

The first resource I found was this thread on the forum tuts4you, here the user extremecoders wrote a few posts on how he unpacked the PyArmor protected file. He edited the CPython source code to dump the marshal of every code object that gets executed.

While this method is great for exposing all the constants, it’s less ideal if you want to get the bytecode, this is because:

- You will have to find the main module code object, since all code objects get dumped, even the ones from modules, etc. it will be more difficult to find the main one.

- The code object won’t have been decrypted yet by PyArmor since that only happens when the

__armor_enter__function gets called, which is at the start of the code object. Since the__armor_enter__function decrypts it in memory it won’t get dumped by CPython.

There are some people that have experimented with dumping the decrypted code objects from memory by injecting Python code.

In this video someone demonstrates how he disassembles all the decrypted functions in memory.

However, he hasn’t found out yet how to dump the main module, only functions. Thankfully he published his code he used to inject Python code. On the GitHub repository we can see that he creates a dll in which he calls an exported function from the Python dll to execute simple Python code. Currently he has only added support for finding the Python dlls for versions 3.7 to 3.9 but you can easily add more versions by modifying the source and recompiling it. He made it so it executes the code found in code.py, this way it’s easy to edit the Python code without having to rebuild the project every time.

In the repository he includes a Python file which will dump all the function’s names to a file with their corresponding address in memory, if there is no memory found it means it hasn’t been called yet so it also hasn’t been decrypted yet.

# Copyright holder: https://github.com/call-042PE

# License: GNU GPL v3.0 (https://github.com/call-042PE/PyInjector/blob/main/LICENSE)

import os,sys,inspect,re,dis,json,types

hexaPattern = re.compile(r'\b0x[0-9A-F]+\b')

def GetAllFunctions(): # get all function in a script

functionFile = open("dumpedMembers.txt","w+")

members = inspect.getmembers(sys.modules[__name__]) # the code will take all the members in the __main__ module, the main problem is that it can't dump main code function

for member in members:

match = re.search(hexaPattern,str(member[1]))

if(match):

functionFile.write("{\"functionName\":\""+str(member[0])+"\",\"functionAddr\":\""+match.group(0)+"\"}\n")

else:

functionFile.write("{\"functionName\":\""+str(member[0])+"\",\"functionAddr\":null}\n")

functionFile.close()

GetAllFunctions()From call-042PE's repository

In the code you can see he added a comment saying the problem he has is that he can’t access the main module code object.

After a lot of Googling I was stumped, unable to find anything about how to get the current running code's object. Sometime later in an unrelated project I saw a function call to sys._getframe(). I did some research on what it does, it gets the current running frame.

You can give an integer as an argument which will walk up the call stack and get the frame at a specific index.

sys._getframe(1) # get the caller's frameNow the reason that this is important is because a frame in Python is basically just a code object but with more information about its state in memory. To get the code object from a frame we can use the .f_code attribute, you will also be familiar with this if you have created a custom CPython version which dumps the code objects that get executed as we also get the code object from a frame there.

...

1443 tstate->frame = frame;

1444 co = frame->f_code;

...From my custom CPython version

So now we have figured out how to get the current running code object, we can simply walk up the call stack until we find the main module, which will be decrypted.

Now we’ve pretty much figured out the main idea of how to unpack PyArmor. I’ll now show 3 methods of unpacking that I have personally found useful in different situations.

The first one requires you to inject Python code, so you’ll have to run the PyArmor script. When we dump the main code object like I explained above the main problem will be that some functions will still be encrypted, thus the first method invokes the PyArmor runtime function so that all the functions needed to decrypt the code objects are loaded, like __armor_enter__ and __armor_exit__.

This seems like a pretty simple thing to do but PyArmor did think of this, they implemented a restrict mode. You can specify this when compiling a PyArmor script, by default the restrict mode is 1.

I haven’t tested every restrict mode out but it works for the default one.

When we try to run this code in our REPL you will get the following error:

>>> from pytransform import pyarmor_runtime

>>> pyarmor_runtime()

Check bootstrap restrict mode failedThis prevents us from being able to use the __armor_enter__ and __armor_exit__.

So the next step I took was contacting extremecoders on tuts4you. He helped me by mentioning that I could natively patch the _pytransform.dll. I also want to thank him for giving me the solution on doing this solely in Python.

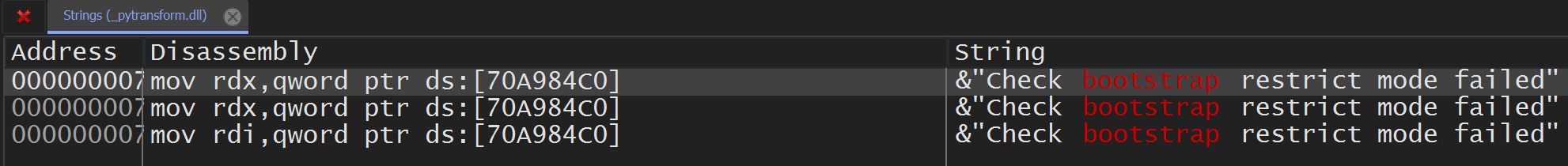

If we open the _pytransform.dll in a native debugger, I chose x64dbg, we will look for all the strings in the current module.

If we filter this now by searching for "bootstrap", we will get the following.

When we watch the disassembly on the first search result you see that there is a reference of _errno indicating that there could be some error raised, a few lines below that we can see the error that we get in Python.

When we just NOP everything from the point of the jump that jumps over the code that triggers the error to the return there is no way that the error could be raised.

Now if we save this and replace the _pytransform.dll you will see that when we try the same code again the error won't happen and we have access to the __armor_enter__ and __armor_exit__ functions.

>>> from pytransform import pyarmor_runtime

>>> pyarmor_runtime()

>>> __armor_enter__

<built-in function __armor_enter__>

>>> __armor_exit__

<built-in function __armor_exit__>Now this is quite tiring if we have to do this for every PyArmor script that we want to unpack, so extremecoders made a script that NOPS the specific addresses in memory in Python.

# Credit to extremecoders (https://forum.tuts4you.com/profile/79240-extreme-coders/) for writing the script

# Credit to me for adding the comments explaining it

import ctypes

from ctypes.wintypes import *

VirtualProtect = ctypes.windll.kernel32.VirtualProtect

VirtualProtect.argtypes = [LPVOID, ctypes.c_size_t, DWORD, PDWORD]

VirtualProtect.restype = BOOL

# Load the dll in memory, this is useful because once it's loaded in memory it won't need to get loaded again so all the changes we make will be kept, including the bootstrap bypass

h_pytransform = ctypes.cdll.LoadLibrary("pytransform\\_pytransform.dll")

pytransform_base = h_pytransform._handle # Get the memory address where the dll is loaded

print("[+] _pytransform.dll loaded at", hex(pytransform_base))

# We got this offset like I showed above with x64dbg, it's the first address where we start the NOP

patch_offset = 0x70A18F80 - pytransform_base

num_nops = 0x70A18FD5 - 0x70A18F80 # Minus the end address, this is the size that the NOP will be. The result will be 0x55

oldprotect = DWORD(0)

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE = DWORD(0x40)

print("[+] Setting memory permissions")

VirtualProtect(pytransform_base+patch_offset, num_nops, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, ctypes.byref(oldprotect))

print("[+] Patching bootstrap restrict mode")

ctypes.memset(pytransform_base+patch_offset, 0x90, num_nops) # 0x90 is NOP

print("[+] Restoring memory permission")

VirtualProtect(pytransform_base+patch_offset, num_nops, oldprotect, ctypes.byref(oldprotect))

print("[+] All done! Pyarmor bootstrap restrict mode disabled")If we put this code a in a file called restrict_bypass.py we can use it like the following, using the original _pytransform.dll

>>> import restrict_bypass

[+] _pytransform.dll loaded at 0x70a00000

[+] Setting memory permissions

[+] Patching bootstrap restrict mode

[+] Restoring memory permission

[+] All done! Pyarmor bootstrap restrict mode disabled

>>> from pytransform import pyarmor_runtime

>>> pyarmor_runtime()

>>> __armor_enter__

<built-in function __armor_enter__>

>>> __armor_exit__

<built-in function __armor_exit__>The second method starts off the same as the first method, we inject the script which gets the current running code object.

Only now the difference is that we won't just dump it, we will "fix" it. By that I mean removing PyArmor from it completely so that we get the original code object.

Since PyArmor has multiple options when obfuscating I decided to add support for all the common ones.

When it detects a script has __armor_enter__ inside it it will modify it so that the code object returns right after the __armor_enter__ has been called.

There is a POP_TOP opcode following the function call, this is used so that the return value of the function is removed from the stack, we just replace it with the RETURN_VALUE opcode so that we can get the return value of the __armor_enter__ function and so that we have the decrypted code object in memory without actually running the original bytecode. See the example below

1 0 JUMP_ABSOLUTE 18

2 NOP

4 NOP

>> 6 POP_BLOCK

3 8 <53>

10 NOP

12 NOP

14 NOP

7 16 JUMP_ABSOLUTE 82

>> 18 LOAD_GLOBAL 5 (__armor_enter__)

20 CALL_FUNCTION 0

22 POP_TOP # we change this to RETURN_VALUE

9 24 NOP

26 NOP

28 NOP

30 SETUP_FINALLY 50 (to 82)Because PyArmor edits the code object in memory the changes will stay even after we exit the code object.

Now we can invoke (exec) the code object. We now have access to the decrypted code object. All that's left now is to remove the PyArmor modifications to the code object, that being the wrap header and footer.

After that has been cleaned we have to remove the __armor_enter__ and __armor_exit__ from the co_names.

We repeat this recursively for all code objects.

The output will be the original code object. It'll be like pyarmor was never applied.

Because of this we can use all our favorite tools, for example decompyle3 to get the original source code.

The third method fixes the last issue with method #2.

In method #2 we still have to actually run the program and inject it.

This can be an issue because:

- it's malware

- the program exits instantly because of some anti debugging

- any other case where you don't have enough time to inject

The third method attempts to statically unpack PyArmor, with which I mean without running anything of the obfuscated program.

There are a few ways you could go about statically unpacking it but the method I will explain looks the easiest to implement without having to use other tools and/or languages.

We will be using audit logs, audit logs were implemented in Python for security reasons. Now ironically we will be exploiting the audit logs to remove security.

Audit logs essentially log internal CPython functions. Including exec and marshal.loads, both of which we can use to get the main obfuscated code object without having to inject/run the code. A full list of audit logs can be found here

CPython added something neat called audit hooks, every time an audit log is triggered it will do a callback to the hook we installed. The hook will simply be a function taking 2 arguments, event, arg.

Example of an audit hook:

import sys

def hook(event, arg):

print(event, arg)

sys.addaudithook(hook)The only way to save code objects to disk is by marshalling it. This means PyArmor has to encrypt the marshalled code objects, so naturally they have to decrypt it when they want to access it in Python.

They, like most other people, use the built-in marshaller. The package is called marshal and it's a built-in package, written in C. It's one of the packages that has audit logs, so when PyArmor calls it we can see the arguments.

The code object will still have encrypted bytecode, but we already managed to get past the first "layer", we can basically re-use our method #2 from this stage as it also has to deal with encrypted code objects. The only difference now is that every code object will be encrypted instead of the ones that would normally already have been ran, like the main code object.

Because in method #2 we inject the code we already have access to all the PyArmor functions like __armor_enter__ and __armor_exit__. Since we try to unpack it statically we don't have that luxury.

As I mentioned above PyArmor has restrict modes, I already showed how to bypass the bootstrap restrict mode since that only gets triggered when we run the pyarmor_runtime() function.

Now we need to run the whole obfuscated file, which includes the __pyarmor__ call. That function triggers another restrict mode so we have to bypass that. First I was thinking that we use a similar method by patching it natively.

A friend helped with that, these are the steps you can do to repeat it. Keep in mind I found a better and easier method.

PyArmor checks if the PYARMOR string is present at a specific memory address in __main__. We need to patch this check. See the image below

Now the better method I found is that PyArmor's restrict mode doesn't check if the main file is directly ran by Python or if it was invoked, so we can simply do this:

exec(open(filename))Of course after we installed the audit hook.

The problem I had was that the audit hook triggered on marshal.loads, but obviously after it had triggered I needed to load the code object myself but that would just trigger it again so I added a check to see if the dumps directory exists. This is dangerous because if there is still a dumps folder left over from before it would just result in executing the protected script without stopping it. We have to find a better way to do that.

EDIT: I recently discovered that I forgot about the part where we need to edit the absolute jumps. This part will cover that.

When need to do this in both method #2 and method #3. When we remove the footer there will be no collions with the indexes.

When we remove the header however it will cause the indexes to shift by the size of the header so we need to loop over all the absolute jumps and subtract the size of the header. That part is fairly easy.

for i in range(0, len(raw_code), 2):

opcode = raw_code[i]

if opcode == JUMP_ABSOLUTE:

argument = calculate_arg(raw_code, i)

new_arg = argument - (try_start+2)

extended_args, new_arg = calculate_extended_args(new_arg)

for extended_arg in extended_args:

raw_code.insert(i, EXTENDED_ARG)

raw_code.insert(i+1, extended_arg)

i += 2

raw_code[i+1] = new_argFrom method #3

We loop through the bytecode and check if the opcode is the JUMP_ABSOLUTE opcode. If it is we will calculate the argument (keeping the EXTENDED_ARG in mind). Then we take the try_start which is the size of the header (it's actually the index of the last opcode from the header, that's why we add 2) and subtract it from the argument of the JUMP_ABSOLUTE opcode.

The hardest part of implementing this was taking care of the EXTENDED_ARG opcodes that we potentially have to add when the argument goes over the maximum size of 1 byte (255). We handle that in calculate_extended_args.

def calculate_extended_args(arg: int): # This function will calculate the necessary extended_args needed

extended_args = []

new_arg = arg

if arg > 255:

extended_arg = arg >> 8

while True:

if extended_arg > 255:

extended_arg -= 255

extended_args.append(255)

else:

extended_args.append(extended_arg)

break

new_arg = arg % 256

return extended_args, new_argFrom method #3

To write this code I first had to understand how the EXTENDED_ARG worked exactly.

This article helped a lot for understanding this opcode.

An instruction in Python is 2 bytes in the more recent versions (3.6+). One byte is used for the opcode and one byte is for the argument. When we need to exceed one byte we use the EXTENDED_ARG. It basically works like this:

arg = 300 # Let's say this is the size of our argumentWe know the maximum allowed is 255 so we need to use EXTENDED_ARG, you would think it'd be like this:

extended_arg = 255

arg = 45That's what I first assumed but after looking at the code that Python generated I noticed it was like this:

extended_arg = 1

arg = 44I was very confused why it was like that since I saw no correlation between what I expected and the reality.The article linked above explained everything.

Python handles the EXTENDED_ARG like following:

extended_arg = extended_arg * 256After seeing this everything was clear since it would mean that

extended_arg = 1 * 256

arg = 44

print(extended_arg + arg)Would output 300.

I applied that logic to the function so that it returns a list of the necessary EXTENDED_ARG opcodes and the new argument value (which would be under or equal to 255).

I then just insert the EXTENDED_ARG at the correct index's.