Lambda syntax: f(x) => y Wikipedia - Lambda calculus:

'Lambda calculus (also written as λ-calculus) is a formal system... based on function abstraction and application using variable binding and substitution. ...'

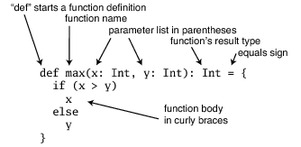

A function has this form:

def name(params): T = body

Here is another example from the Scala book explaining a function:

The most common way is defining a function as a method. In my very first steps session you had to implement a simple calculator: Worksheet: Calculator Exercise

In this exercise there are functions defined as methods for add, subtract, multiply, and divide.

Unlike Java for example Scala is less restrictive on naming conventions. It allows special characters like the operators '+' and '*'. Take a look at Int's ScalaDoc.

object ScalaHackSession {

// Double.*(Int)

2. * (2) //> res0: Double(4.0) = 4.0

// Int.*(Int)

2 * 2 //> res1: Int(4) = 4

// Float.*(Int)

2f * 2 //> res2: Float(4.0) = 4.0

// Float.*(Double)

2f * 2d //> res3: Double(4.0) = 4.0

}

Source: https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9910724

In Scala this is good practice, while this is bad practice in Java:

def add(a: Double, b: Double) = a + b

In Java usages of curled braces, long variable, and method names are good practice. On the other hand Scala - as a functional languages with normally very few lines of code - conventions are focused on brevity. Please read more on Scala conventions here.

Similar to local variables that can be defined within a scope like a method you can also define local functions: https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9603298

Another possibility of using local functions is to define private methods. Compared to private functions a local function is visible only within a block - in this case in the method block.

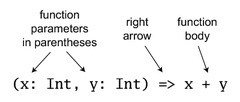

Similar to anonymous inner classes you can define anonymous functions: a function literal is a function with no name in the Scala source code (glossary) and looks like this:

For example you can define a function returning another function: https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9617230

Here the defined random function returns a function literal. The function literal is then assigned to randomInt and called later on. Another possibility is to call a returned function directly as shown in the example.

Let me explain that in more detail by our add function from the calculator example and change it into a function literal.

[Quiz] Refactor this add function by defining a function literal:

def add(a: Double, b: Double) = a + b

[Answer] The solution is: def add = (a: Double, b: Double) => a + b https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9619358

As you can see you can call it like 'addFunctionLiteral(2,3)'. It might be not obvious but the method addFunctionLiteral returns a function literal. It is also possible to assign it for instance to a val and then call the function literal. Examining how Scala compiles theses functions you need to understand the difference between function, partial function, and partially applied function.

The classes from Function0 to Function22 are traits 'Function N traits'. If you want to know more about traits read here. For now it is sufficient to know that it is a hybrid of Java Interfaces combined with the capability having code implementations as well as allowing some sort of 'multiple inheritance' (=mixin composition). Another way to implement the add function is defining a new singleton object AddFunction and extending it from Function2: https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9620003

The first two Double types in the 'extends Function2[Double, Double, Double]' defines the input argument where the last Double type specifies the type of the output in the apply method. When you call AddFunction.apply(2,3) you get 5 as a result. A more convenient way is to call it in function style using AddFunction(2,3). In this case the compiler will call the apply function. On Stack Overflow there is a good explanation for the apply and unapply method.

Actually a function literal is equivalent to an implementation of FunctionN. It is compiled as an anonymous class of type FunctionN. Here is a good blog about how Scala compiles to Java like methods, singletons, and function literals. This great blog series goes into more details about function literals as first-class citizens.

Mathematically a partial function f(x') => y is a subset of a function f(x) => y where x' is a subset of x. In Scala you use for this the PartialFunction trait: https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9620714

The PartialFunction has along with the apply method a isDefinedAt method. This allows the caller to (manually) check the input arguments first before applying a partial function. Read more about partial functions here.

Please do not mix up a partial function with a partially applied function.

A partially applied function is...

'... A function that's used in an expression and that misses some of its arguments. For instance, if function f has type Int => Int => Int, then f and f(1) are partially applied functions.'

A possible implementation of an increment function may look like this:

def inc(a: Double) = a + 1

But if you look at it the inc function it is just a special logic compared to our existing add function. Would it not be nice to re-use the add function? Like this: https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9623039

In general when you call a function and pass all arguments then you apply that function to the arguments. So when you call add(2,3) then you apply add to the arguments 2 and 3. Using underscore is just a placeholder for one or more parameters. In this case you are partially applying a function to some parameters - but not all - with specific values and leave the remaining parameters by using underscores.

This blog describes it well about function, partial function, and partially applied function while this blog describes how partially applied functions are compiled.

Before I go deeper and explain about higher-order functions and curried functions it helps when you understand the differences between functions and methods and how a function value is compiled by binding a function or method to a val or var.

A function value is a FunctionN instance. FunctionN are usually expressed as function literals. Similar to the difference between a class and an object/instance a function literal is a definition in your source code and a function value is an instantiation of a function. Take a look at the function literal example from the last blog: https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9619358

Here I have defined a method addFunctionLiteral containing an anonymous FunctionN implementation. In the next line we have an instance respectively a function value addFunctionValue.

There are quite some differences between a method and a function. Calling a function f(x) is just syntatic sugar because it is compile as f.apply(x) where a method m(x) stays as it is. It is possible to assign a method to a val or var: https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9642182

In this case an anonymous FunctionN is instantiated (as a function value). In case the method requires more than one parameter you can use underscore for a list of parameters: 'add ' instead of 'add(,_)'.

It is also important to know that in case a method is defined with default parameters it gets lost in a function value. A step-by-step explanation of what is compiled when using functions, methods, and function value is described in this blog.

A closure is a function object capturing free variables. An advantage of using closures is re-using functions like our add function. Here we can define a new increment function and re-use the add by capturing one parameter as a 'closed' reference using a free variable 'incSize' and define the second parameter with a fix value of '1': https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9638686

Function literals can be used in many ways like as a return value and as an input parameter of a function or method. Functions expressed as function literals are first-class functions. Functions taking functions as parameters are called higher-order functions.

One example is defining a log function where you can pass any function as shown in this worksheet: Worksheet: functions

Here the logOperation does a print before executing the function parameter.

Hava a look back in the previous session regarding control structures. In the for expression worksheet you had to print all count numbers and in another exercise to print even count numbers in each line: Worksheet: Control Structures

[Quiz] Using higher-order functions we can define a method with two parameters. Refactor this for expression by defining a method taking two parameters:

def printCount(filter: Int => Boolean, count: Int) = ???

[Answer] The solution looks as follows: https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9663696

Here is another good example taken from Odersky's book providing helper functions for file name validations:

File matcher functions without high-order functions and duplicate code (Example from: Programming in Scala, Chapter 9.1: Reducing code duplication):

def filesEnding(query: String) =

for (file <- filesHere; if file.getName.endsWith(query))

yield file

def filesContaining(query: String) =

for (file <- filesHere; if file.getName.contains(query))

yield file

def filesRegex(query: String) =

for (file <- filesHere; if file.getName.matches(query))

yield file

Source: https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9912329

As you can see all 3 functions are similar except the matching condition by using different method calls on a String: endsWith, contains, and matches.

Scala's approach to solve this is passing a matching function. The function has a file name as an input and a boolean as an output checking the filename with the appropriate String method:

f: String => Boolean

File matcher functions using high-order functions (Example from: Programming in Scala, Chapter 9.1: Reducing code duplication):

//high-order function with a function as input

private def filesMatching(matcher: String => Boolean) =

for (file <- filesHere; if matcher(file.getName))

yield file

//high-order function usages:

def filesEnding(query: String) =

filesMatching(_.endsWith(query))

def filesContaining(query: String) =

filesMatching(_.contains(query))

def filesRegex(query: String) =

filesMatching(_.matches(query))

Source: https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9912433

Currying is (Wikipedia)...

'... the technique of transforming a function that takes multiple arguments (or a tuple of arguments) in such a way that it can be called as a chain of functions... Uncurrying ... can be seen as a form of defunctionalization. It takes a function f(x) which returns another function g(y) as a result, and yields a new function f'(x,y)...'

Simply said when you have a function f(x,y) the curried function would be f(x)(y) and vice versa f(x,y) is the uncurried function of f(x)(y). Currying turns a function with multiple arguments into a (curried) function with one argument - whereas the curried function itself returns a function requiring the next parameter. How can you do that? Guess what: function literals!

The currying process for f(a,b) => y looks like this:

f(a,b) => y

f(a) => f(b) => y

[Quiz] Refactor our add method by returning a function literal accepting another Int parameter and returning the result of both parameters:

def first(a: Int) = ???

[Answer] What you see here is that you can call the first function and then use the returned function value (as often as you want) or directly call both functions like first(2)(3). https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9664609

In Scala there is another way to define a curried function instead of using function literals in the style of 'f(p1)(p2)(..)(pn)': https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9664952

This is syntactic sugar and a convenient way to define curried functions. Either way you define it like that or use function literals: the Scala compiler treats both definitions the same.

There are of course other ways of how you implement a curried function like using local methods and partially applied functions. Have a look at the curried function examples for add(x,y).

'Hmmm... but what is the advantage of a curried function?', you may ask. One main reason is separating special and general respectively different concerns into functions.

[Quiz] Have a look at the above printCount function again. Refactor the function taking two parameters into a curried function.

[Answer] Changing the higher order function into a curried function is just syntactic sugar and requires minimal change in the method signature: https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9666595

Basically the printCount function is separated into a general part where you log and another special part where you determine in which case you want to log.

Of course you can solve this by using higher order function and partially apply it: https://gist.github.com/taitruong/9668031

Here is another more complex example for a curried functions.

Functions

- Define some functions: http://www.artima.com/pins1ed/first-steps-in-scala.html#step3

- Scala Functions: https://gleichmann.wordpress.com/2010/10/31/functional-scala-functions/

- How are functions treated in Scala? http://java.dzone.com/articles/how-are-functions-treated

- How do you define a type for a function in Scala? http://stackoverflow.com/questions/1853868/how-do-you-define-a-type-for-a-function-in-scala

First-class functions

- "A function literal is compiled into a class"

- http://www.artima.com/pins1ed/functions-and-closures.html#8.3

Higher-Order functions

- Control Abstraction: http://www.artima.com/pins1ed/control-abstraction.html

Currying

- "A curried function is applied to multiple argument lists"

- http://www.artima.com/pins1ed/control-abstraction.html#9.3